In London, there is Soho; in New York, Chelsea and Greenwich Village; and in San Francisco, there is the Castro. In Sydney, there is Darlinghurst and, more specifically, Oxford Street. These are neighbourhoods of large cities that have, since at least the 1950s and often earlier, developed a reputation as queer spaces.

In more recent years, those reputations have begun to fade and the enduring meanings of the “gaybourhood” have come into question.

But what each of these places represents is the centrality of urban space to the emergence of visible, “out and proud” lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer identities and communities.

Read more: Friday essay: on the Sydney Mardi Gras march of 1978

Queer Sydney in the ‘Golden Mile’ era

The peak years of Oxford Street’s queer life extended from the mid-1970s until the mid-1990s. In the years after the second world war, many gay men in Sydney socialised in CBD hotels, including the Hotel Australia.

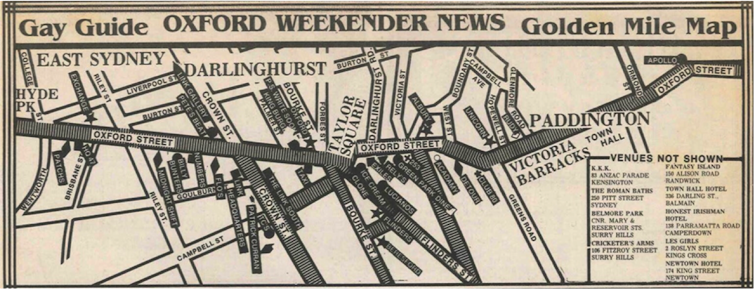

A guide to the ‘Golden Mile’ published in the Oxford Weekender News, one of many ‘bar rag’ newspapers that circulated the 1980s queer scene. Image: author-provided

The first LGBTQ clubs on Oxford Street were Ivy’s Birdcage and Capriccio’s, which both opened in 1969. By the beginning of the 1980s, Oxford Street was home to a string of bars, clubs, saunas and cafes and had become known as Sydney’s gay “Golden Mile”.

The emergence of this gay heartland represents extraordinary social change. Male homosexuality remained illegal in New South Wales until 1984. The homosexual men socialising in 1950s CBD hotels were required to do so with discretion – the consequences of discovery could be devastating.

In contrast, the queerness of a venue like Capriccio’s was defiantly visible and undeniable. As more venues were opened along the Golden Mile, the street itself became a gay space, as did the surrounding neighbourhoods where LGBTQ people – particularly gay men – made homes in the terraces and apartments of Darlinghurst and Paddington.

A simple walk along the street became an act of participation in an emerging community.

Ivy’s Birdcage at 191 Oxford Street was one of Darlinghurst’s first drag bars. Sydney Pride History Group, Image: author provided

Members of a marginalised social group were thus using urban space to resist oppression and build a community. For some, this produced a kind of utopia. In an interview with Sydney’s Pride History Group, DJ Stephen Allkins described his first visit to the Oxford Street disco Patch’s as a teenager in 1976. He remembers:

"I was home. That was it. It was the most fabulous place I’d ever been in my life … It’s full of gay people and they’re all dressed to the nines. They’re not hiding under a rock … They’re expressing and happy."

Finding a place in the queer community

But these feelings of joy at having found such a space can be complicated by a range of factors. The gay community was certainly not free from sexism, racism and transphobia, meaning that some within the LGBTQ community were granted far easier access to these spaces than others.

Indeed, although Golden Mile-era Oxford Street included venues popular with lesbians, including the women-only bar Ruby Reds, the surrounding neighbourhood was more identifiably gay than lesbian.

Inner-west suburbs including Leichhardt and Petersham were far more significant urban spaces in the lives of many queer women. Lesbian share-houses in these neighbourhoods became central sites of feminist politics, activism, sex and romance.

Penny Gulliver, a resident of legendary 1970s share-house “Crystal Street”, has remembered that women “who were just coming out, because there was nothing like a counselling service then, they’d come to Crystal Street”.

Into the new millennium, Oxford Street’s place as the gay heart of Sydney became less certain. As LGBTQ businesses failed and venues closed, questions emerged as to whether a community now more a part of the mainstream still needed its own spaces.

For a time, King Street in Newtown dominated as a queer alternative. In 1983 gay publican Barry Cecchini took over the Milton Hotel on Newtown’s King Street, renamed it Cecchini’s and launched it as the area’s first gay venue. Shortly after, the Newtown Hotel, just across the road, also became a gay pub. Cecchini told the Sydney Morning Herald in 1984 that gays were leaving “the scene” of Oxford Street looking for a “more cosmopolitan mix” in Newtown.

Through the following decades, venues including The Imperial in Erskineville (made famous as the site from which three drag queens launched their adventures in a bus named Priscilla) and the Sly Fox in Enmore, home to a popular lesbian night, further developed the area’s queer reputation.

Protecting queer space

In recent years, however, a range of factors, including changes to licensing laws, have produced significant challenges for queer socialising in that neighbourhood.

Newtown sits outside the zone of the so-called “lockout laws”. Late-night partiers who might once have ventured to Kings Cross are instead heading to pubs along King Street, and reports of anti-LGBTQ abuse and violence have increased.

In response, a campaign called “Keep Newtown Weird and Safe” has attempted to maintain the queer meanings of this urban space.

Despite changes in Oxford and King streets, efforts to keep Newtown “weird” highlight the continued value of urban space to LGBTQ communities. Indeed, among a younger generation, new forms of queer identity continue to inspire the search for spaces in which to celebrate difference.

In pockets of the inner west, for example, young queer, transgender and genderqueer people are creating spaces of activism, partying, performance and everyday life. This new generation is exploring the fresh possibilities of queer identity and developing their community. Access to urban space remains central to this.

Like the city itself, the LGBTQ community continues to be less a fixed entity than a process of movement, adaptation and change.

Scott McKinnon, Vice-Chancellor's Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Wollongong

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.