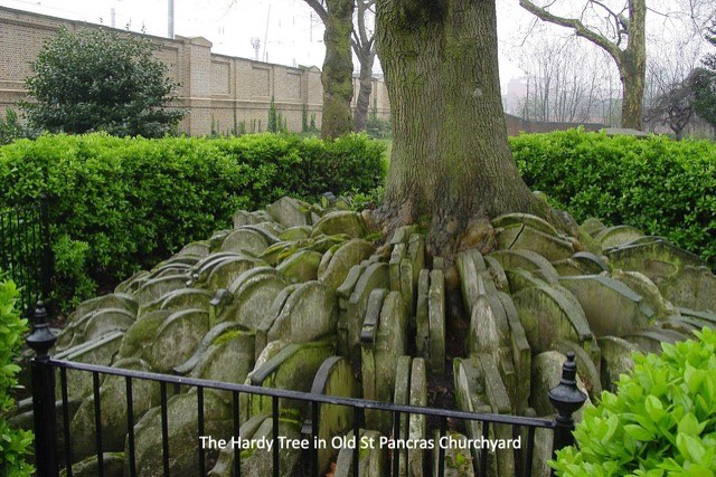

Between Christmas and New Year, the ‘Hardy Tree’ fell in Old Saint Pancras Churchyard, London. When the Midland Railway was pushed through to Kings Cross Station in 1865 the old cemetery was destroyed and the project architect, Thomas Hardy (before he was a celebrated writer), had the inspiration to stack the relocated gravestones tangentially around the base of an Ash tree, symbolising both death and life.

The attribution seems apocryphal however, as the tree was planted after Hardy's time working on the project. What is more surprising, for me at least, was that Thomas Hardy, greatest English novelist of the second half of the 19thC, originally trained as an architect. Who knew?

Not me; and I was once somewhat of a Hardy aficionado. As a miss-placed student in an upper-class, church-run, all-boys school, I found solace in Hardy’s writings and ideas: agnosticism (not to say atheism), rejection of polite society and championing the natural life and the working-class.

I got an A in fifth form for my essay on Tess of the D’Urbervilles (although Mr. Francis had to explain to callow youths that Tess was effectively raped). Not long after, I tried to court a girl by writing an essay on Far from the Madding Crowd for her to submit. She got a B; I was dropped.

My affection for Hardy was helped as I imagined we had a connection through our birthplaces, him outside Dorchester, me at Weymouth; I’d never heard of anyone famous or creative coming from the rather unfancied Dorset, which he eulogized as the centre of a mythical Wessex, the setting for many of his novels. But through all that I never knew he practiced my chosen profession of architect.

Thomas Hardy was born in 1840. His father was a builder/stone mason. His well-read mother home-schooled Hardy until eight, he then studied Latin at Mr Last’s Academy for Young Gentlemen but, being too poor for a university education, at sixteen he was apprenticed to James Hicks, a local architect.

Hardy was a keen reader, thinker and was beginning to write. Henry R. Bastow, a Plymouth Brethren and fellow architectural apprentice at Hicks, gave cause for robust debates about religion. Bastow was baptised as an adult which Hardy considered, but decided against. Not long after, both Bastow and Hardy left Hicks and went separate ways, but maintained a long correspondence on religion and other matters.

Hardy moved to London in 1862, enrolling as a student at King's College. He won prizes from the RIBA and the Architectural Association and joined Arthur Bloomfield's practice as an assistant architect. He worked on several churches, which is how he came to be excavating a graveyard for a railway extension.

Hardy was now writing novels, including the unpublished, and lost, Poor Man and the Lady, as a way of addressing issues of class divisions, his feelings of social inferiority, and his increasing uneasiness with the Anglican faith. He was attracted to the works of John Stuart Mill, particularly his essay On Liberty.

In 1867, tiring of London which he blamed for ill-health, he returned to Dorset, settling in coastal Weymouth. He continued architectural work but also dedicated himself to writing. Whilst helping the restoration of St. Juliet in Cornwall, Hardy met his future wife, Emma Gifford, the love of his life and exquisite muse, particularly after her death.

Hardy wrote serials, a popular form of fiction at the time. In A Pair of Blue Eyes, the protagonist was left dangling from a cliff at the end of one episode. Hence the term cliff hanger. But it was not until the publication of Far from the Madding Crowd in 1874 that Hardy had sufficient funds to cease working as an architect and be a writer full-time.

Ironically it was his success as a writer that enabled him to design his magnum opus as an architect, some ten years later. His own house on the outskirts of Dorchester is a Georgian proportioned and Queen Anne rendered villa called Max Gate. Construction is variously attributed to his father and brother and was substantially extended in 1895. It is now a National Trust property.

There is only one architectural work by Hardy in his hometown of Dorchester, a Vestry and Chancel for the Church of St Peter. There are few National Trust properties in this rather ordinary town in the Dutchy of Cornwall. But regular readers will recall an earlier ToT column discussing the ever troublesome and much criticised new town of Poundbury on its outskirts, the controversial plaything of King Charles III.

Back to nineteenth century Dorchester. In 1860, the aforementioned Henry R. Bastow leaves Hicks, and his friend Hardy, to emigrate to Tasmania, where he wins a competition for the Hobart Town Hall, never built. In 1866, he moves to Melbourne and becomes a draftsman with the Victorian Water Supply Department; later an architect and civil engineer with the Railways Department.

The Education Act in 1872, which provides for free, compulsory and secular primary school education throughout Victoria, requires hundreds of new schools. Bastow is appointed architect and surveyor for the newly formed Education Department, responsible for the design and construction of these schools.

In 1873, a competition is held for a variety of school designs and prizes are awarded for schemes, many are adapted by Bastow for different sizes and sites, adding details and designing many more himself. Most early schools were in a Victorian Gothic Revival style, (long established for educational buildings - see the early work at Sydney and Melbourne Universities; in contrast to Classicism for civic work).

Later schools are in Queen Anne (such as Prahran State School) or Tudor styles. By 1885, over 600 schools had been built across Victoria, many of them still functioning as such, and 25 of them designed by Bastow are listed in the Victorian Heritage Register.

In 1883 the Education Department’s architecture branch becomes part of Public Works, and Bastow is a senior architect working on a wide variety of public buildings as well as schools. In 1886, he becomes Chief Government Architect of Public Works, a position he holds for four years. His public buildings were said to be marked by simplicity and restraint.

For much of this time he maintains a correspondence with Thomas Hardy, although the latter eventually tires of the exchanges on religion, and the letters cease. Bastow retires, moves to Central Victoria as an apple orchardist, and designs a simple home with a meeting room for his Brethren fellows.

One curiosity is that Bastow does not appear in The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture by Philip Goad and Julie Willis. For ten years I have frequently referred to this extensive and exceptionally well researched book, always fancying I could spot a lacuna. Now I have, I’m not sure how to approach Australia’s two most pre-eminent architectural researchers and writers. Perhaps I should suggest that the second version include Henry Bastow, correspondent with one of the greatest English novelists, and architect of over 600 schools and many public buildings.

Tone Wheeler is an architect / the views expressed are his / contact at [email protected].