“Well may we say, ‘God save the Queen’ for nothing will save the Governor General”, E.G. Whitlam, 1975

The activists who burnt the front porch and doors to the Australian Museum of Democracy on 30 December last year chose it for symbolism and opportunity. As the ‘Old Parliament House’, it represents white oppression to many indigenous, a government that is repudiated by ‘sovereign citizens’; and it is wide open to the public, unlike the fortress of the ‘New Parliament House’ up the hill.

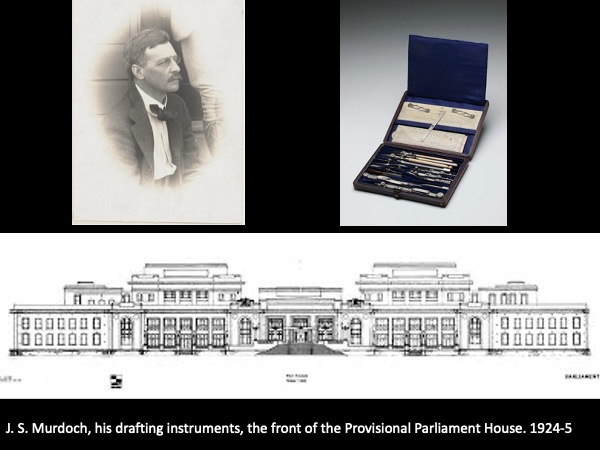

The political symbolism is easily understood: the Provisional Parliament House was important as the seat of federal parliament for more than sixty years. However, the symbolism of the building itself is not so readily apparent, but it is of utmost architectural importance. I would argue that it is one of Australia’s most significant designs; and yet its importance, and that of its architect, J. S. Murdoch is little recognised outside architectural historians

John Smith Murdoch, a Scottish émigré, almost single handedly established the style that became known as ‘Federal Capital’, one of the few regional styles in Australia, and the Provisional Parliament House was its apotheosis. You would think that he would be better celebrated, but he is as forgotten as his buildings are under-appreciated. Firstly, we will examine the design ideas of that beautiful building, and then examine how he got to those ideas.

Provisional Parliament House

The Provisional Parliament House, as it was originally known, became the ‘old’ one when the ‘permanent one’ on Capitol Hill was opened in 1988. Designed and built in three years (1924-27), Murdoch was dismissive of some of its charms, mostly because of the haste he felt, and yet has all the traits of his best architecture.

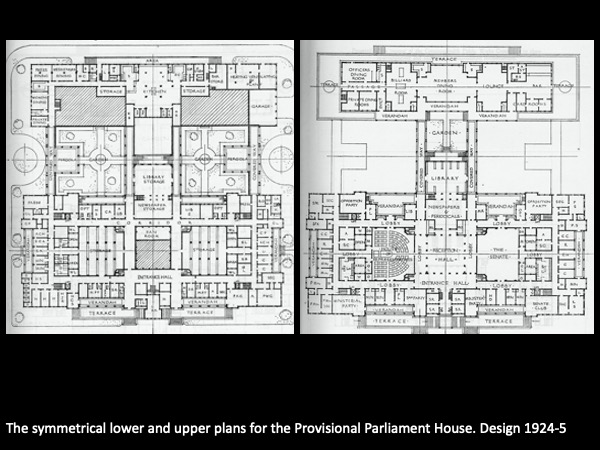

The plan is simple and bifurcated as befits the two houses of parliament and their attendant spaces. The central approach has a welcoming grandeur: up a double flight of broad stairs to deep recessed portico (seared in the psyche of the older voter for the quote at the top). The entry is modest, a result of both costs and Murdoch’s Scottish parsimony, but it leads to the ‘Entrance Hall’ which is part of the ‘Reception Hall’, the largest room in the complex. Soon known as ‘Kings Hall’ it works as a ‘mezzanine’ level that gives access to the chambers and all the key rooms.

This directness speaks of desire for the building to be easily open to all Australians (before considerations of physical accessibility), so that one can access the member’s and senator’s rooms and the two chambers directly, a delightful quality, almost naïve, in contrast officiousness and security that are the hallmark of the (permanent) Parliament House up the hill. No wonder the tent embassy and protests enjoyed such longevity on the OPH forecourt.

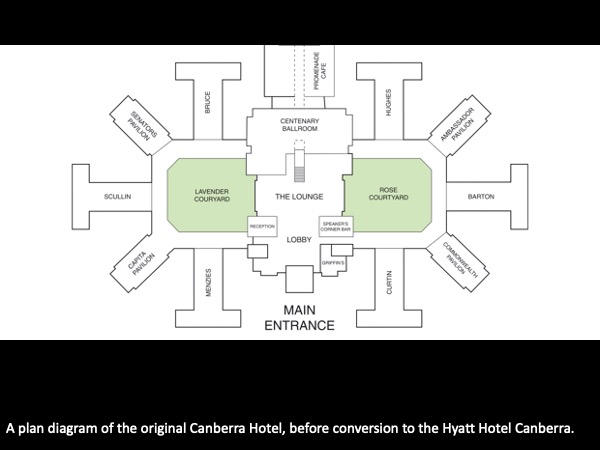

There is a hierarchy of rooms in the front, main, building from centre (top lit and ventilated) to the edges (smaller with large vertical windows for light and ventilation). The plan is then arranged around two courtyards that provide contemplation spaces, protection from harsh weather, security, as well as an extended external surface area for windows (before the invention of air conditioning). Courtyards, such an environmentally sensible typology in cool temperate / dry summer conditions, were a mainstay of his plans.

The buildings are raised a quarter of a storey above the ground, on locally made natural red bricks (the brickworks was one of Canberra's first industries, opening in 1915). From the start Murdoch had used the raised ‘piano nobile’ or main floor to increase the scale and emphasise its importance of his buildings. It also allowed for ventilation under the timber floors and access for the nascent power and communications technologies.

Above the red brick base, the buildings are white – giving the appearance of stark, strong and sharp forms against the deep blue unpolluted skies, in contrast to darker recessive tones in the local houses. And crucially the white reflects the summer heat at a time when there was little insulation and no mechanical means of cooling.

The facades are symmetrical along Georgian lines, with deep reveals to vertically proportioned windows, both forms providing protection against the sun. The openings are also modest, in defense against the extreme the cold (well known to a Scotsman). There are porticos and porches as in-between spaces to protect from the harsh sunlight and rain, particularly for the openings into the courtyards.

The internal courtyards were formally landscaped to provide a sanctuary and intimacy against the vast external landscape. The paths were well worn by politicians doing deals in private, and the quality of the gardens – mostly European derived and planted – gave rise to an ‘Englishness’ in early Canberra landscapes (before the nationalism of gum trees post WW2).

The building has a visual and spatial character borne of a different age, bit it is redolent of a desire to make a special place and spaces, of an understanding of the climate, both physical and political, and a confidence in ourselves. That the 1988 Parliament House draws so many cues from the ‘quicky’ provisional one is testament to its ideas. So how did Murdoch arrive at this point?

J.S. Murdoch

Born in 1862, he was trained and articled in Scotland, emigrating with his parents in 1884, at the age 22, to escape a depression. He soon found work with the Queensland government as an architect and in 1904 he takes a position as a Senior Clerk in the newly formed Commonwealth Department Home Affairs (later Works and Railways), rising to architect in 1914 and chief architect 1919-29. He designs numerous Commonwealth buildings in Sydney, Melbourne, and Perth, but his attention is soon to be almost wholly devoted to the development of Canberra.

Before there is a plan for Canberra, or even a competition for one, he designs the key infrastructure of the Powerhouse and the Water Pumping Station at the Cotter dam in 1911. He designs the first major house in the district, the Residency for David Miller, the administrator of the Federal Capital Territory in 1913, the year Walter Griffin and Marion Mahoney win the design competition.

He travels to the USA and convinces Griffin to take up the position in the Federal Capital Authority, as the ‘Federal Capital Director of Design and Construction’. Despite their early friendship (he greets him on arrival in Sydney), Griffin and Murdoch have a falling out. Whilst Griffin and Mahony takes five years to finalize his plans, Murdoch is busy establishing buildings that will become the 'Capital Federal' style.

The Griffins want to hold an international competition for the design of the Parliament House, the key building in their plans. Two competitions are held in 1914 and 1916, and the judges include eminent overseas architects Otto Wagner and Louis Sullivan.

However, political in-fighting and WW1 put paid to any conclusion to the competitions.

In 1918 as the war is ending, Murdoch is asked to design an internment camp for 3,500 German citizens. He designs and organises the build in three months near the Molonglo River, but in the end only 600 are held in detention for three months. We can only wish that our current Government in Canberra could have enabled someone of Murdoch’s effectiveness to build the quarantine camps we have needed in the last two years.

In 1920, the Griffins leave Canberra having had the masterplan gazetted but built nothing more than a gravestone at the newly formed Duntroon and established the windbreak of Haig Park. The architecture that will define the city will be created by his arch enemy, Murdoch.

By 1921 the government based in Melbourne is keen to proceed with Canberra, and a Federal Capital Advisory Committee is formed, chaired by the eminent architect John Sulman. Housing for politicians and public servants transferring to Canberra takes two forms: lodges or hotels, and free-standing houses. Murdoch has a hand in both.

A housing competition, with Murdoch as one of the judges, is won by Oakley Parkes and Sutherland, establishing a style for the higher-end housing in soon-to-be up-market Forrest. In 1922-4 he designs the Hotel Canberra (later extended as the Hyatt), Gorman House in 1924-5, the Hotel Kurrajong in 1926 and the Hotel Acton in 1927. In each he is developing the parameters of Canberra’s Federal Capital style.

In 1923 the government decides to move Parliament to Canberra and establishes the ‘Seat of Government Act’, and a more urgent operation starts with the Federal Capital Commission, chaired by Sir John Butters established in 1925. And they commission the first of what we would now call workers’ housing.

Murdoch then designs smaller versions of the Forrest houses: red brick bases, off-white or dark cream stuccoed or painted brick work, gable, hip and valley roofs in Marseilles tiles. Small in size, with one or two bedrooms, they have deep veranda spaces facing the street, modulated in form to give them an air of something bigger.

Murdoch is commissioned to design the Provisional Parliament House to sit on Griffin’s land axis, below the intended Permanent Parliament House, which in turn will be below the ‘Capitol’ building on the crown of the hill (where Parliament House is eventually built). By 1927 all is in readiness for the opening of the Parliament in Canberra; Murdoch has been able to design, orchestrate and see it built in under three years.

Murdoch designs two schools: Telopea Park High in 1922-3, and Ainslie Infants in 1927, having all the characteristics he had created for Federal Capital style: buildings with courtyards, symmetrical pavilion styles, lifted up on red brick bases, white walls with red tile roofs, well-proportioned vertical windows for light and air. And he has one more significant role to play.

Australian War Memorial

After WW1 in 1926 the government instigates a design competition for a War Memorial. In another blow to Griffin’s scheme, they choose the base of Mount Ainslie, the site originally intended for a ‘Casino’ – in those days a ‘cultural or pleasure palace’ - a foretaste of how war veterans and gambling were to combine.

Murdoch is one of the judges, and at his instigation no winner is announced. Rather, two primiated schemes are chosen and asked to collaborate, Emil Sodersten and John Crust. Their collaboration, urged on by Murdoch, creates Canberra’s other major building. The importance of this work (and the tragedy about to befall it) is discussed here.

The Tent Embassy

Politicians, not architects, have fenced off new Parliament House to keep people away rather than to invite people in, the barren dry-paved forecourt, a defensive area intended to prevent protest. The tent embassy could never have been established on the concrete hardscape of the forecourt of the new Parliament House. Security would have prevented any approach that might lead to an attempt to burn it in protest.

I would argue that Murdoch’s influence and his buildings, Provisional Parliament House in particular, helped create Canberra’s open quality in its fledgling democracy. The forecourt of the Provisional Parliament House, its steps and portico, are open spaces in which crowds could gather to hear an address or to protest, which made it a perfect site for the Aboriginal Tent Embassy that arrived in 1972 and celebrates 50 years next Wednesday. That fire, at least, has not gone out.

Researched and written by Tone Wheeler. Views expressed solely those of the author, not held or endorsed by A+D. Comments may be addressed to [email protected].