Adwo/Shutterstock

Adwo/Shutterstock

Stefan Caddy-Retalic, University of Adelaide; Kate Delaporte, University of Adelaide, and Kiri Marker, Universität Wien

Large areas of concrete and asphalt absorb and radiate heat, creating an “urban heat island effect”. It puts cities at risk of overheating as they are several degrees warmer than surrounding areas.

One of the best ways to keep our cool is to maintain leafy streets, parks and backyards. But in some cities, trees are being chopped down faster than local councils can replace them. Some councils are also fast running out of land to plant trees.

Most of the damage happens on private land. Usually it’s a result of large blocks being subdivided or undeveloped land being opened up for more homes.

Cutting down trees for urban development is well within the law. But tree-protection laws are weaker in some parts of Australia than in others. To ensure our cities remain liveable, some laws will have to change.

Many housing subdivisions, such as this new estate in Tyabb, Victoria, leave little room for trees. Drone Alone/Shutterstock

Many housing subdivisions, such as this new estate in Tyabb, Victoria, leave little room for trees. Drone Alone/Shutterstock

Why cities need trees

Beyond just providing shade, trees reflect heat into the atmosphere. They also cool the air by releasing water through pores in their leaves, acting like evaporative air conditioners.

Trees provide many other benefits such as removing pollutants, limiting erosion and improving public health.

The influential 3-30-300 rule for green cities, proposed by Dutch researcher Cecil Konijnendijk, states:

-

you should be able to easily see three trees from the window of your house or workplace

-

cities should have at least 30% overall tree cover

-

you should have a green space with trees within 300 metres (or a three-minute walk) of your house or workplace.

Brisbane leads the way when it comes to the percentage of tree cover in Australian cities. ChameleonsEye/Shutterstock

Brisbane leads the way when it comes to the percentage of tree cover in Australian cities. ChameleonsEye/Shutterstock

Why urban trees need better laws to protect them

How do Australians cities stack up against the 30% canopy goal of the 3-30-300 rule?

Brisbane leads the way, with 44% of the City of Brisbane council area blanketed in trees. Hobart also makes the grade, with analysis of aerial imagery from Google showing a tree canopy of 34%.

Other cities have some work to do to meet the benchmark. Recent aerial image analysis shows Perth sitting at 22% cover.

The NSW Department of Planning reported Sydney’s canopy cover as 21.7% in 2022. The Victorian Department of Transport and Planning reported 15.3% canopy cover across metropolitan Melbourne in 2018.

Green Adelaide reports today that Adelaide’s canopy is a mere 17%. That’s worrying for a city so vulnerable to urban heat.

While it can be tempting to compare canopy results, this needs to be approached with caution. The two main techniques for estimating tree canopy, airborne LiDAR (using laser sensing) and analysis of aerial photographs, can produce different results. Even LiDAR data from the same location but analysed at different resolutions can be quite different.

But what’s concerning is that some cities seem to be losing trees very rapidly. An analysis of aerial photographs by Nearmap shows Adelaide suburbs are fast losing trees. A 2021 Conservation Council report estimates Adelaide is losing about 75,000 trees per year across the city. Most are on private land.

Local councils have been planting several thousand trees each year, but are running out of places to plant them. Requirements for clear space on road verges and around powerlines pose major limitations.

If we want greener cities, we also need to take a critical look at the laws on tree removal.

Our team at the University of Adelaide produced a 2022 report on tree-protection laws across Australia. The state government commissioned us to verify a claim that South Australia’s tree-protection laws were the weakest in the nation. We compared state and local council regulations, and the claim turned out to be true.

What’s wrong with the SA laws?

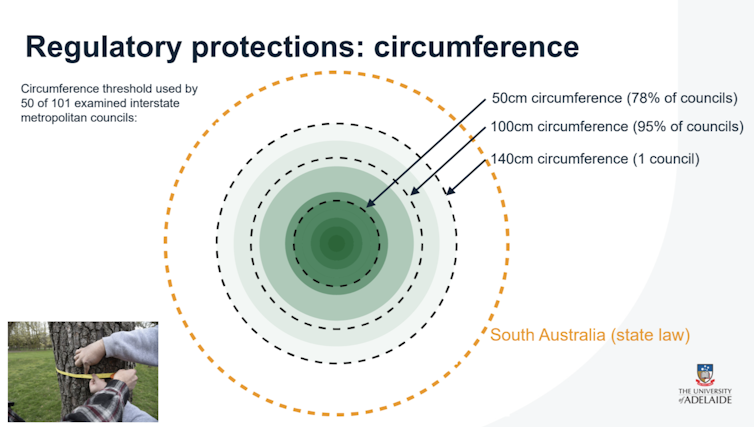

One consideration is the size thresholds used to define trees as “regulated” or “significant”. Of the 101 metropolitan councils outside SA that we investigated, 78% considered trees with trunk circumferences of more 50cm deserving of legal protection. And 95% applied protection when circumferences exceeded a metre. In South Australia, only trees with twice that trunk size get any legal protection.

Just over half of surveyed capital city councils outside South Australia protected trees based on circumference. Of those, 95% used a circumference of 1m or less and 78% a circumference of 50cm or less. Source: Urban Tree Protection in Australia 2022

Just over half of surveyed capital city councils outside South Australia protected trees based on circumference. Of those, 95% used a circumference of 1m or less and 78% a circumference of 50cm or less. Source: Urban Tree Protection in Australia 2022

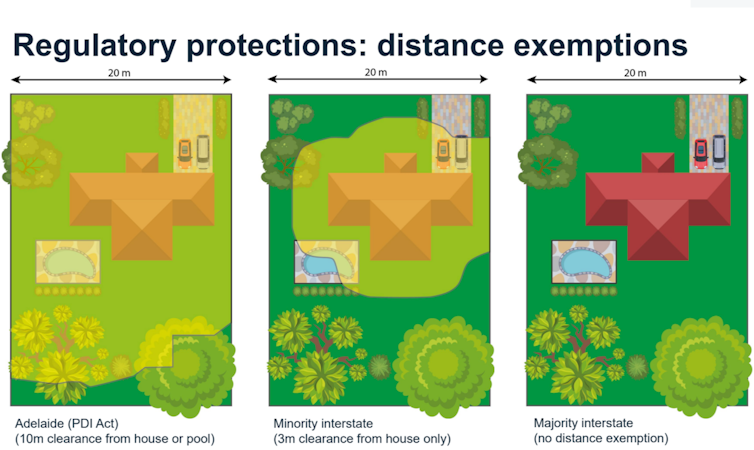

Another issue is distance exemptions. In South Australia, large trees that would otherwise be protected may be removed if they are within 10 metres of a house or pool. This rule is regularly used to clear entire residential blocks – after all, nearly all trees on suburban blocks are within 10m of a house or pool.

A majority of the interstate councils had no distance exemptions to speak of.

Of the 101 local councils surveyed outside South Australia, only 16 allowed protected trees to be removed if they were within 2-3m of a house. Source: Urban Tree Protection in Australia

Of the 101 local councils surveyed outside South Australia, only 16 allowed protected trees to be removed if they were within 2-3m of a house. Source: Urban Tree Protection in Australia

So what needs to change?

Our findings were among the drivers of a South Australian parliamentary inquiry. An interim report was released last October. It includes sensible, straightforward recommendations to improve the state legislation.

The report suggests reducing the circumference at which trees qualify for protection. It recommends adding crown spread as another criterion. It wisely recommends deleting the distance exemption.

The report also weighs in on fees and fines – the “bottom line” deterrents and punishments for doing the wrong thing. It recommends increasing the fee for legally removing “regulated” trees from $489 to $4,000, for example. However, the value that large trees provide to the community is regularly estimated at hundreds to thousands of dollars per year.

Similarly, a recommendation to introduce a $40,000 fine for illegally removing a “significant” tree pales in comparison to laws interstate. In NSW, illegally removing protected trees can incur fines of over $1 million. To deter big developers, fines must be larger than what they might regard as a reasonable “cost of doing business”.

The report’s recommendation to pay fines and fees into an Urban Forest Fund to grow canopy near areas of tree removal is a good one. Planting trees on the other side of town doesn’t help residents (or biodiversity) when trees are removed locally.

Cities can draw inspiration from each other

Adelaide’s climate is shifting from a temperate Mediterranean climate to a semi-arid one. Semi-arid climates are less able to grow many temperate plant species and tend to have less vegetation overall. To create an extensive and healthy tree canopy for future generations, we need to act fast and think critically about what we’re planting (and protecting).

We hope the South Australian government will follow the inquiry recommendations, so the state’s tree laws are on par with those of other states and cities.

Cities like Melbourne, which are also becoming warmer and drier, can look toward Adelaide as a future climate analogue. Urban planning is often about learning from other cities and adapting their strategies to local contexts.

To cope with the twin challenges of climate change and rapid urban growth, Australian cities need to work together to actively develop greening strategies. If we don’t, our cities will become hot, dry and barren.

Stefan Caddy-Retalic, Ecologist, School of Biological Sciences, University of Adelaide; Kate Delaporte, Senior Lecturer, School of Agriculture, Food and Wine, University of Adelaide, and Kiri Marker, Science Communications Coordinator, Universität Wien

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.