The greatest conceptual and environmental artist of the last 60 years died this week. Together with his wife Jeanne-Claude, Christo created memorable artworks and installations, mostly involving huge areas of cloth that wrapped buildings or danced through the environment.

This is not an obituary; there are excellent ones from the BBC and the New York Times. Rather, this is a note about Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s first major wrapping project, on the coastline at Little Bay south of Sydney, that can stand for the vast impact of their work.

Christo Javacheff (1935–2020), a refugee from Bulgaria, and Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon (1935–2009), born in Morocco of French parentage, had been working together for 10 years since their marriage in 1959, using just Christo’s first name, in what we would now call a ‘brand’ when they made ‘Wrapped Coast, Little Bay’ in 1969.

Their reputation for innovative projects, including protesting the Berlin wall by illegally blocking a street in Paris with 400 oil barrels, had brought them to the attention of John Kaldor, a nascent Australian art patron. Kaldor invited them to create one of their ‘wrapping’ projects, for which they had made numerous small-scale proposals. They jointly agreed to wrap a length of Australian coastline in the grounds of a public hospital.

In this first, as in all of their later projects, they eschewed grants, raising the funds to execute the work by making small artworks depicting the larger. These collages of pencil and ink drawings over photographs and plans often included samples of the proposed material; a 3D image pressed flat into a frame. Not only a way of raising funds, these works were essential in exploring ways of thinking about the project. Many of these explorations are in collections of public Australian galleries.

Kaldor’s background in fabric helped source the one million square feet of woven fabric normally used to prevent agricultural erosion, and 35 miles of polypropylene rope which would hold it in place (Christo always used imperial measurements from their adopted home in New York). More difficult was finding a team that could install it.

They approached a number of universities and art schools that declined. Their good fortune was to approach Marr Grounds, in his first year of teaching first year at the University of Sydney. Marr, son of Sir Roy Grounds, had repudiated his father’s approach to architecture, and trained firstly as a US Marine and then as an environmental artist at UC Berkeley, in its heyday of environmental art. He had been instrumental in the building of a hippy colony called ‘Drop City’ in Southern Colorado.

Given the twin, seemingly oxymoronic, backgrounds to Marr’s training he recognized immediately the potential to be involved in the organisation of one of the great art projects of the century. He asked his first-year students if they would like to be involved, and 14 of them volunteered.

As a student, whose high school was more interested in Cadets’ guns than art, I went to see the artwork under construction to ask if I could contribute. Told that I was too young, I left without knowing that the workers clambering all over the rocks were the university students that would become some of my closest friends when I started architecture studies the following year, in part motivated by Christo’s art.

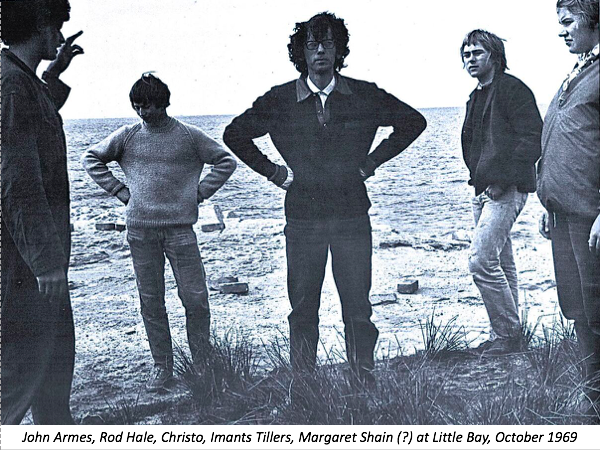

Among them was John Armes, a tall and handsome student whose family had arrived in Australia from Rhodesia. John became my friend, organising our first share house, and told me much of what I know of the installation work at Little Bay, together with some discussions with Marr Grounds with whom I later worked on a project. My comments rely on their recollections, rather than any direct involvement.

The official site lists over a hundred installers, including professional mountaineers, yet in the photos we see only a small crew of amateur students who laboured for weeks to install the cloth, held in place by ropes fastened by gun-fired fasteners. The students were shown how to use the ‘weapon’ by a company representative and immediately given a license. Christo quickly realized that Armes possessed a talent for organization and management, one he used in a lifelong career as a country architect in Yass, before his death in 2016. He became a de facto foreman amongst the students including many who went on to become well known architects and artists, including Imants Tillers, his first brush with international art, where he is now well known.

Christo quickly realized that Armes possessed a talent for organization and management, one he used in a lifelong career as a country architect in Yass, before his death in 2016. He became a de facto foreman amongst the students including many who went on to become well known architects and artists, including Imants Tillers, his first brush with international art, where he is now well known.

The wrapped coast was opened to much acclaim, somewhat surprising given the conservative nature of Australia at the time (the swinging sixties happened in the swinging 70s in Australia). It took an hour to walk the two-kilometre length of the artwork, which remained for two weeks before being dismantled for recycling (as Christo did with all his work).

John Kaldor brought Christo to Australia before the rest of the world knew his wrapped works, before the Reichstag, the Pont Neuf, California’s ‘Running Fence’, the surrounded islands, and many more. Great art needs a great patron and Kaldor has made an incalculable contribution to Australian art life. He, more than anyone, will be saddened by Christo’s passing.

Lastly, some comments on art and collecting.

John Kaldor sponsored another 50 years of Kaldor Public Art Projects, celebrated in exhibitions across Sydney last year, and in a beautiful text. Many of those artworks were similar to Christo’s: ephemeral with no lasting physicality. All we have after the artwork goes is photos, which is a perfect reason to seek out Kaldor’s book.

There is a beautiful irony that Christo and Jean-Claude financed their projects by making tiny artworks. They made some of the biggest artworks the world has ever seen, involving hundreds of workers, out of some of the smallest, most personal works. And those works were legally reproduced and are still available, and collectible.

Lastly, I have two copies of the official poster for Little Bay and I contacted John Kaldor last year to ask him to sign one, my personal commemoration of a great work he organized. He demurred, suggesting he would organize for Christo to sign when he was next in Australia. Christo couldn’t come, but I still want Kaldor’s signature, not for its value to art, but for its value to me.

Little Bay was a first for Australia in art. We don't have many, but we should celebrate the fact that Christo's great career in wrapping things started on a little beach in Sydney. One critic explained Christo’s wrapped works as ‘revealing things by concealment’, and he revealed not only the beautiful form of our coastline, but the beauty of collaborative work, brought about by concerted patronage.

Vale Christo, you added so much to Australian cultural life.

Tone Wheeler is principal architect at Environa Studio, Adjunct Professor at UNSW and is President of the Australian Architecture Association. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and are not held or endorsed by A+D, the AAA or UNSW. Comments can be addressed to [email protected].