Gone are the days when guide books only covered choice city centres. Away from them you could wander around not knowing what to see, where to eat, where the nearest toilet or vintage clothes shop was.

Now, insights in these books extend far wider. Hardie Grant’s Tokyo Precincts (one of a series) tells me that the suburb I lived in in the early 1980s, Koenji, is famous for the late night live music bars and their long-haired decidedly non-salary men, which I had chanced upon.

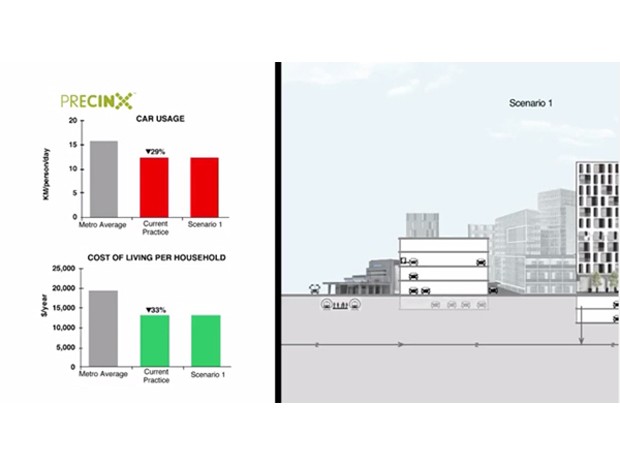

In an era where people want to know more about a city than just its key attractions, it is fitting that the 2015 Judge’s Choice Weapon of Mass Creation award winner is an urban planning and design tool called CCAP Precinct (also known as PRECINX), developed by sustainability consultancy Kinesis in collaboration with UrbanGrowth NSW. Announced at the Green Building Council of Australia’s recent Green Cities conference, the tool predicts the environmental, economic and social impacts of residential, commercial and mixed-use developments.

The software’s metrics include data on greenhouse gases, potable water, transport and land–use, embodied and operational energy, water and stormwater, capital and recurrent costs and household operating costs. It is already used by government land-use organisations and some of Australia's largest developers and utilities.

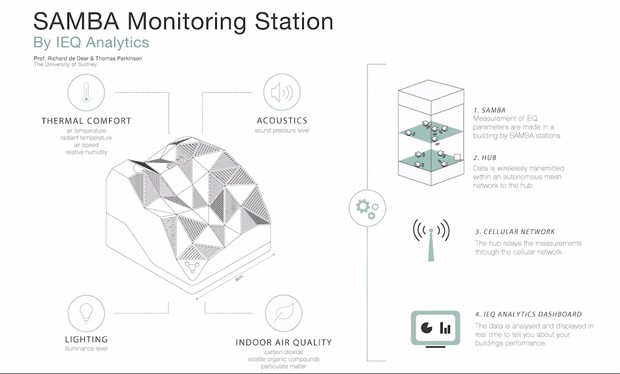

The focus is also in our buildings, and this is reflected in the People’s Choice Weapon Award which went to the University of Sydney’s IEQ Lab for its SAMBA device, which measures indoor environmental quality in buildings. (The IEQ Lab is within the university’s Faculty of Architecture, Design and Planning.)

Small sensors monitor factors from thermal comfort, indoor air quality, humidity and air speed, to light levels, acoustics and carbon dioxide concentrations, and then relay this information back to a central computer for further analysis. This is all in the cause of IEQ improvements leading to healthier, more productive workplaces and to tenant satisfaction.

Small sensors monitor factors from thermal comfort, indoor air quality, humidity and air speed, to light levels, acoustics and carbon dioxide concentrations, and then relay this information back to a central computer for further analysis. This is all in the cause of IEQ improvements leading to healthier, more productive workplaces and to tenant satisfaction.

Nothing, however, is a foregone conclusion. For all the evidence amassed, professionals have to first be convinced of it, and then to act on it. Certainly, the mood was buoyant with high hopes for connections within the industry, to other industries and to the community. As GBCA CEO Romilly Madew said, “We now operate in a borderless world of technological wizardry – a place where people, ideas and capital are unrestricted. This has far-reaching implications for our cities – and for our industry.”

Belief and emotions are important parts of the equation. To keynote speaker, urbanist Larry Beasley, “what your city feels like is a determining factor in its success or failure. (We need to) put the soul back into the city ... bringing back the human touch.” Rob Adams, Director City Design at City of Melbourne, talked about creating streets where people want to be; Kylie Legge, Director of Place Partners, of everyday street life, sitting and walking that can “give a place its identity”; Chris White, Executive Director Facilities and Sustainability at the University of Melbourne, of how people flocked to food markets on campus.

We can be inspired by nature; be hopeful that the purchase of green bonds may continue; learn from Aboriginal people about connection to place and to the environment, but most importantly is recognising, as Madew said, the “need to drive cultural and structural change ... (that) encourages connections over competition”.

Melbourne Lord Mayor Robert Doyle reiterated how “making our city more sustainable is directly connected with our future prosperity”, a sentiment sharpened by self-proclaimed conscious capitalist, Craig Davis, who bluntly asked, “What is the point of having sustainable buildings if the people aren’t?” Or as Lend Lease’s CEO of Property, Tarun Gupta, put it, we need to place “great obligation” alongside “great opportunity”.

Deborah Singerman runs her own writing, editing and project managing consultancy specialising in the urban built environment and community. @deborahsingerma