Permanent formwork systems have become an attractive alternative to conventional masonry block, precast concrete and in situ building methods for both builders and designers in Australia, particularly in the multi-residential space.

Suppliers and manufacturers of the systems herald them as the next big thing in construction, promising quicker project turnarounds, reduced costs, and cleaner and safer construction sites.

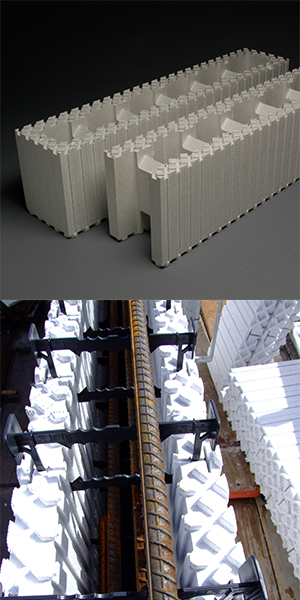

While they do vary slightly in their size, assembly methodology and capability, systems generally come as lightweight hollow panels or blocks that join together to form walls that are then core filled with concrete and steel.

They require little bracing compared to in situ pours, erase the need for bricklayers and their materials, and require no specialised trades to erect—although in some instances warranties are voided if accredited installers are not used.

While the systems are comparatively new, they have been around for long enough now to provide sufficient time for the industry to assess their performance against promises from suppliers. So we put the question out there to the industry—do they live up to the hype and are they suited to single dwelling construction?

GOING FOR GROWTH

When asked, Cameron Lovett of Sydney-based construction outfit, Lovett Custom Homes initially said yes. But that soon changed to a “well, sort of”, and then an “actually, not quite”.

“Look, I love the idea of the system, or using anything that can replace the messy trades of brick and blockwork on site,” he says.

“But I just don’t think they’re quite there yet.”

Like a lot of Australian residential builders, Lovett and fellow Sydney builder Mitchell Levett of Cadence & Co, one of Sydney's premier residential design and construction companies, are seeing permanent formwork systems on construction drawings more and more, and are also aware of their increasing popularity around building sites in general.

“We almost always use Dincel now,” says Levett, who has worked on some of the most expensive new houses on Sydney’s Northern Beaches including the recently completed Palm Beach House (pictured below).

“And I don’t see us ever going back if we can help it.”

Palm Beach House by Cadence & Co employs the Dincel Construction system for structural walls and retaining walls.

Dincel (pictured right), as Levett refers to, is one permanent formwork option available in Australia that claims to be a fast, cheap, and easy alternative to block/brickwork and precast and in situ concrete building methods.

Dincel (pictured right), as Levett refers to, is one permanent formwork option available in Australia that claims to be a fast, cheap, and easy alternative to block/brickwork and precast and in situ concrete building methods.

It comes as a set of lightweight hollow polymer panels, floor tracks and specialist pieces that click together to form a waterproof structural wall that is then core-filled with concrete and steel. It comes in either 100 or 200mm thicknesses and has built-in vertical conduits which enable services (except some plumbing) to be installed after all structural elements have been completed, without the need for chasing.

AFS has a similar version called Rediwall (bottom right) and, like Dincel, it is also becoming an increasingly popular among Australian designers. It’s offered in 150 or 200mm thicknesses and is erected in a simple channel track system, but unlike Dincel it is not advertised as fully waterproof.

There are others as well which are attracting the attention of some of Australia’s leading architects, some with high insulating properties and others with easier-to-finish substrates. Ritek's XL Wall system (middle right), which has been used by Reg Clarke Architect (see bottom) and Steele Associates Architects to award winning effect, is one, while Insulated Concrete Forms (ICF) are another altogether.

Unlike PVC versions, Ritek’s systems use fibre cement sheets for the outer layers of the walls which provide a more traditional surface to finish. These sheets are separated by plastic spaces and bonded to an aluminium track which Ritek guarantees won’t rust. The Thermal Wall version also includes an integrated thermal insulation layer which helps it achieve a healthy R-Value of 4.0.

“You can just tell that companies like Dincel and the like are in high-demand and growing fast. They show up to site with brand new trucks and are always talking about how busy they are.” – Cameron Lovett, Lovett Custom Homes.

Made popular in America, ICF’s are also making inroads into the Australian market. They come as a set of polystyrene blocks that click together like Lego and laid horizontally like traditional blockwork. The EPS provides insulating properties and is also easily cut with a hot knife or grinder to chase services.

Zego Building Systems’s ICF (right) is seeing increasing uptake in Australia, particularly by eco architects and designers, and was used on the recently completed Blue Mountains House by Blue Eco Homes (pictured above) which was the recent recipient of a 2016 HIA Green Smart Award. It features a dovetail groove for render and plasterboard support which solves some of the finishing issues associated with PVC permanent formwork.

Zego Building Systems’s ICF (right) is seeing increasing uptake in Australia, particularly by eco architects and designers, and was used on the recently completed Blue Mountains House by Blue Eco Homes (pictured above) which was the recent recipient of a 2016 HIA Green Smart Award. It features a dovetail groove for render and plasterboard support which solves some of the finishing issues associated with PVC permanent formwork.

It comes in 300mm heights and doesn’t need to sit on a slab rebate which makes it easy to make standard wall sizes like 2.7 and three metres.

Another that’s new to the Australian market is Eco Block, an American-born insulated foam wall system similar to Zego which goes further by incorporating structure, vapour barrier, and battens into one system.

Thermacell and Insulbrick are other highly trusted ICF’s that have been used throughout Australia.

IRONING OUT THE ISSUES

Like a lot of designers, both Lovett and Levett were first attracted to permanent formwork because of its associated benefits, and although they’ve come across a few issues with the system since, they still suggest that the positives far outweigh the negatives. Some of the problems they have run into are a result of inexperience with the system, but they believe most of the responsibility lies with manufacturers who have exaggerated the positives of their products.

These shortfalls have mainly been around speed of construction, bracing requirements, sizing restrictions, waterproofing performance and ease of erection.

“First off, I don’t believe they’re waterproof,” says Levett, who insisted on this despite CSIRO tests that show that Dincel is in fact completely waterproof and guaranteed by Dincel if installed by an accredited installer.

“We’ve had so many problems with water getting into the channels and filling up that we’ve even had to drill out holes in the bottom to empty them of water.”

“We now waterproof, no matter which system we use.”

The promise of “minimal bracing” and “easy to install” are also cases of choice words according to Lovett whose high-end residential projects feature a lot of custom windows and doors.

“Propping at every window, door, T-intersection and on top of walls can take a lot of time, and we often have to prop full height gaps in a wall because the panels don’t meet perfectly in the middle,” he says.

“And feeding corner, horizontal and vertical bars isn’t as simple as it looks.”

To be fair, manufacturers like Dincel, Ritek, Zego and AFS do offer joiner, male/female adapter and spacer panels to solve the very problem Lovett first described, and using systems like Zego, which is a horizontally-laid block system, basically erases this issue.

To explain further, Lovett follows manufacturer directions by building his formwork from the corners in. Because they come in set widths, in Dincel’s case 333.3mm, they don’t always meet in the middle. As mentioned, manufacturers are aware of this and offer spacers and joiners as solutions, but they too come in set widths so naturally you can run into the same problem.

“They’re not always perfect and it’s too time consuming to make up a custom panel when a joiner or spacer doesn’t work so we just back prop and fill the whole wall,” says Lovett.

“Manufacturers also recommend building walls that fit their products, but of course this isn’t something residential architects necessarily want to hear or do.”

“Manufacturers also recommend building walls that fit their products, but of course this isn’t something residential architects necessarily want to hear or do.”

Erecting from scaffolding is also out of the question says Lovett, who likened an unfilled Dincel wall to a boat sail on a windy day.

“Trying to click a three metre PVC wall together from scaff in a howling southerly is suicide,” he says.

“We only work from decks.”

The structural side of the Cronulla House by Reg Lark Architect (right) involved the use of the Ritek XL wall system. A key benefit on the system is its reduced wall thickness compared to conventional masonry. Photography by DLPhotography

FINISHING CORRECTLY

Finishing a polymer based permanent formwork wall can mean rethinking your waterproofing, adhesives and coatings, cladding materials and methods. We’ve heard stories of tradies scuffing the surfaces of the PVC walls with a grinder just to get their render to stick, and others about render actually falling off the wall because adhesives couldn’t hold the weight of a traditional render build. But the problem here could lie in the render products being used.

Polymer renders that are essentially sand and cement based renders that come in bags are not suitable for PVC formwork systems and only appropriate for absorbent masonry substrates. Several Australian coating companies now offer products that are guaranteed to stick to PVC formwork, some without the need for polymer primers. These are all acrylic-based coatings and include Astec Armatex, Novatex, Dulux Acratex and Taubmans Armawall.

Another alternative is Zego’s system which has a patented dovetail groove that enables render and plasterboard to mechanically adhere to the foam. This means no roughing up of the surface is required prior to finishes being applied and no screw holes to set and sand on the plasterboard because it can be stuck directly to the wall. On the flip side of that, sticking plasterboard to the foam is untraditional and will require new skills separate to simply screwing, setting and finishing.

“I am not totally convinced just yet, there are still a few issues that need to be ironed-out. Then I think it has the potential to take over the industry entirely.”

Contrary to some manufacturer claims, Zego managing director Scott Evans also recommends waterproofing basements, no matter which system you use.

“I’ve been a builder for 35 years and I wouldn’t take the chance in a basement,” he says.

“We have to justify why we recommend waterproofing our walls, but at the end of the day we all hear the stories about other systems failing.”

Like the PVC versions, Zego should be waterproofed with a bitumen free membrane and there are several products available on the market that suit most permanent formwork systems. Kuniseal, Xypex and Drizoro’s Maxseal Flex membranes are a just a few.

HERE TO STAY

That all said, both Lovett and Levett, and others that we’ve spoken to are certainly on board the permanent formwork freight train. Using permanent formwork for a basement construction instead of a column-slab structural system meant an overall reduction in concrete and steel for a recent job Levett worked on, so he saved both time and money there.

Lovett is currently employing Dincel in lieu of brick for a reverse veneer exterior wall at his newest job in Clontarf, NSW and says this system has great potential as a green building solution considering its thermal mass, waterproofing capability and environmental credentials.

They’re both also erecting exterior walls at a rapid pace and getting to know how to best sequence trades to come in and work with the walls before or after the concrete pour.

Both agree that the systems are faster to erect, easier to handle, provide a cleaner worksite and can be cheaper in some instances. They only hope that some of the previous problems are solved and that custom panels and more options for curved walls become part of the manufacturer product offerings in the future.