Dean Landy is a partner in Melbourne architecture firm, ClarkeHopkinsClarke (CHC), as well as the founder and director of the One Heart Foundation, a not for profit organisation working to alleviate poverty in Africa.

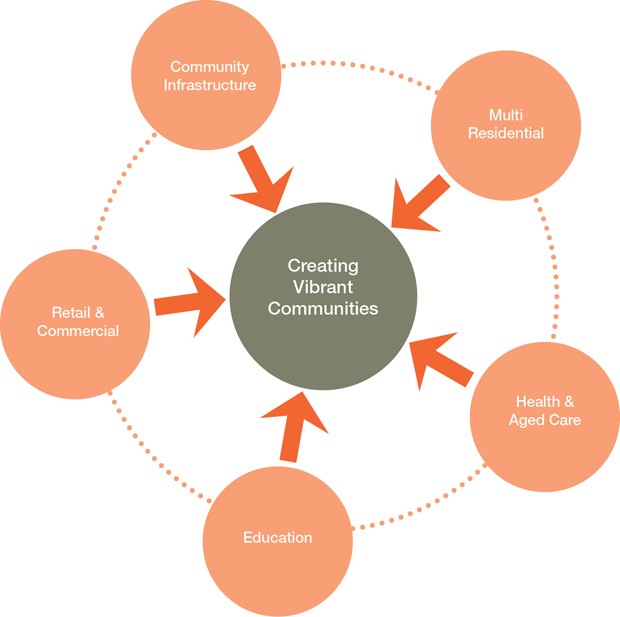

With over 10 years’ experience as a registered architect, Landy has planned and designed projects that span the Retail & Mixed Use, Multi-Residential, Commercial and Community Infrastructure sectors. He received the ARBV Award for Architectural Services in 2009, and as a fervent community advocate is involved in the Creating Vibrant Communities research undertaken by CHC.

Following the first part of our interview with him about why he is planning to run from poverty, we asked him to tell us more about his research, what the Place Evolution Process means, and some of his top tips for masterplanned communities.

What is the Creating Vibrant Communities research, and why did you start it?

Creating Vibrant Communities (CVC) started as an idea about how we could enrich the outcomes of the town and village centres that we are actively designing. This started a process of detailed and ongoing research into what we, as architects and urban designers, can do to make positive change through urban design now and in the future.

CVC is informing ClarkeHopkinsClarke’s overarching approach and highlighting opportunities around how the design community can rethink the process of creating new places and communities to ensure new greenfield, brownfield and urban consolidation projects become more financially, environmentally and socially sustainable places to live.

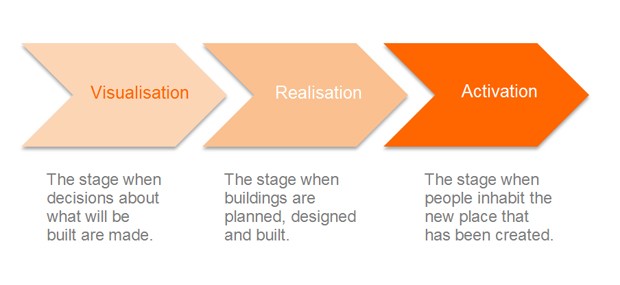

Our current research is rethinking the way new places evolve and trying to set up a process that can be replicated to ensure a more creative and holistic view is taken when designing new places from the initial idea, or the visualisation stage, through to completion and activation by new residents. We call this the ‘Place Evolution Process’.

This idea has gone beyond just research. We are currently working on publishing and conducting valuable interviews to develop a strong resource base and are looking to broaden the discussion in the design community to help contribute to our overall understanding for different stakeholders needs.

Tell us more about the ‘Place Evolution Process’. What is the architect’s role in it?

In September I spoke at the 7th International Urban Design Conference. My topic was "Creating vibrant communities in Greenfield suburbs”. This was the first time anyone from our team has spoken publicly about our research, which aims to improve the urban design processes between government, developers and the community.

We have noticed over the years that the discourse around urban development tends to focus on ‘what’ should be achieved rather than ‘how’ to achieve it and therefore we have set about developing a process and ‘toolkit’ that would support positive outcomes. This diagram helps breaks in down.

Architects and urban designers typically get involved during the Realisation stage noted above, however, I believe there is an opportunity to play a much broader role as a type of community advocate.

By behaving as a catalyst and facilitator of relationships between commercial, government and community stakeholders, greater value can be created for all parties throughout these stages, with the end result being a better place for people to live.

Greater collaboration and the involvement of broader stakeholder groups opens unforeseen opportunities for innovative or simply, contextually-appropriate solutions.

Typically, relationships between developers, designers, local government and the community are somewhat disconnected and sometimes strained during this process, however, taking an inclusive, collaborative and consultative approach can unlock greater value for all stakeholders.

St Germain is a community that is being designed with the ‘Place Evolution Process’. Tell us more.

St Germain is a new greenfield community by visionary developer Gordon Gill, which is being developed within the City of Casey, a fast developing growth area of the South Eastern urban corridor of Melbourne. It has recently been approved by the Planning Minister Hon. Matthew Guy, and is also a Demonstration Project for the Metropolitan Planning Authority. We are well into the overall planning but, in relation to our ‘Place Evolution Process’, it is still in the visualisation phase.

Images: CHC

St Germain has been masterplanned with a strong focus on providing a vibrant and sustainable mixed use community. The project features a unique planning initiative that is driven by the early delivery of key infrastructure projects around a village square such as a large medical centre and shopping centre to start contributing to the overall target of 3500 jobs, and enabling more people to live and work in the same community. Community facilities, retirement living and diverse housing options will soon follow once construction starts in 2015.

The new village square and park will create a distinct sense of place, quality urban infrastructure and amenities, and start to build on the desired sense of community.

What are some tips you’d give to other designers and architects when approaching masterplanned communities?

The following tips reflect the valuable insights that the Creating Vibrant Communities research has contributed to my practice, together with key expertise developed through my experience on diverse master planning projects:

-

Design a place for people foremost. Although parking and traffic related issues need to be resolved well, they shouldn’t be the primary focus.

-

Consider a longer term vision of the town center, or the new community, that is being created. This should be done from the outset to ensure there is a real mixed-use focus, not just retail aspects. Ensuring community, entertainment, education and health facilities are all considered will lead to a more sustainable town centre as it evolves.

-

Broaden stakeholder consultation groups from an early stage. This will ensure the broadest ideas possible are captured, helping make the new place unique and starting to build on the community’s sense of ownership.

-

Become a catalyst for opportunities and a voice for future residents. Discuss with the client/developer alternative ideas to build on their needs as well as ensuring more diverse local town centres. Go as far as creating the connections between the different stakeholders.

-

Think more broadly than just one target demographic ie: young children should be in mind through to older community members. Creating vibrant places where kids can play and older members can feel comfortable and safe with the services they need is an essential element to consider. By ensuring diversity of housing options, developers and designers can cater for more than just the assumed family with 2.4 kids, but also consider the needs of single parents in smaller dwellings, retirees wanting to maintain their independence, younger and older residents, people of varying mobility, as well as multiple generations of families.