Shigemi okano/Shutterstock

Shigemi okano/Shutterstock

If climate change makes you want to want to stay in bed all day and forget the world outside then I have some bad news. About 28% of global CO₂ emissions can be traced to the energy generated to light, cool and heat buildings, while a fifth of the UK’s emissions come from heating and powering homes. So a good chunk of your carbon footprint can be laid down before you’ve even left the house.

And that’s just the emissions that governments tend to count. Much of housing’s greenhouse gases come at other stages in a home’s life, including construction and demolition. These are called “embodied emissions”, and can make up as much as 90% of the whole-life emissions of some buildings.

“What I mean here is the carbon emissions involved in making, renovating and then eventually dismantling the building,” says Francesco Pomponi, vice chancellor’s research fellow at Edinburgh Napier University.

This includes everything from mining the materials for the cement to chopping down the trees for the floorboards to transporting everything to the building site to digging the foundations; and then later from knocking the building down to disposing of its constituent parts.

There are likely to be an extra 2 billion people on Earth by 2050, with most being born throughout Asia and Africa. Developing countries will need hundreds of millions of additional homes over the coming decades, while global emission will need to fall by 60% to keep average warming below 2°C.

In this edition of the Imagine newsletter, we shore up the home front in the fight against climate change. There may be no escape from the crisis enveloping our world, but the dream of better, greener housing could help us all sleep better at night.

What is Imagine?

Imagine is a newsletter from The Conversation that presents a vision of a world acting on climate change. Drawing on the collective wisdom of academics in fields from anthropology and zoology to technology and psychology, it investigates the many ways life on Earth could be made fairer and more fulfilling by taking radical action on climate change.

You are currently reading the web version of the newsletter. Here’s the more elegant email-optimised version subscribers receive. To get Imagine delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe now.

First, let’s ditch concrete

Concrete is a wonder material, but like most of the innovations behind modern life’s conveniences, it’s carbon intensive. Fired bricks need temperatures higher than 1,000°C to cause chemical changes that give the material strength, and it’s as high as 1,450°C for cement. Just producing cement is thought to account for between 5-10% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Since most new homes will be built in the developing world, experts agree that a greener concrete substitute will have to be affordable, attractive and made from locally sourced ingredients. But perhaps “green” isn’t the right word. Alastair Marsh, a research fellow in civil engineering at the University of Leeds, and Venkatarama Reddy, a professor of civil engineering at the Indian Institute of Science, believe that soil could be the perfect component for geopolymers – a naturally strong and durable alternative to cement.

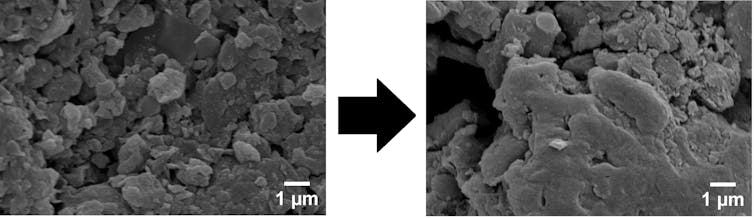

This electron microscope image shows the transformation of montmorillonite clay, left, a common component of soil, into a geopolymer, right. Alastair Marsh

This electron microscope image shows the transformation of montmorillonite clay, left, a common component of soil, into a geopolymer, right. Alastair Marsh

-

How it works – Soil is taken from beneath the valuable surface layer and mixed with chemicals similar to those found in household cleaning products to dissolve the clay minerals into their constituent atoms. A playdough-like mix is formed that can be shaped in brick moulds. During firing at 80-100°C, the dissolved atoms rearrange to form a geopolymer, stabilising the remaining soil.

-

Brown is green – Soil-based geopolymers can be fired at lower temperatures and their ingredients don’t need to be shipped long distances. Depending on the conditions, these bricks could have half the carbon emissions of concrete, and a quarter of the amount produced by conventional fired bricks.

-

Back to basics – Earth-based housing has been the norm in many parts of the world for thousands of years, so there is a rich cultural history behind this idea in most places.

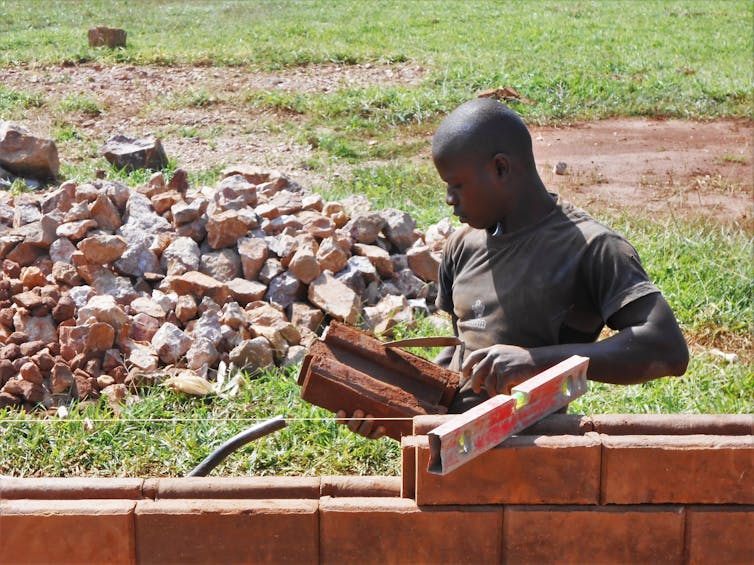

The soil brick is stabilised which makes it more durable, and it does not need to be heated at extremely high temperatures like traditional bricks and cement. Haileybury Youth Trust, Author provided

The soil brick is stabilised which makes it more durable, and it does not need to be heated at extremely high temperatures like traditional bricks and cement. Haileybury Youth Trust, Author provided

Read more: 'Supermud' bricks could help tackle the world’s housing crisis and cut carbon emissions that cause climate change

Then let’s talk about heating

Bricks and mortar are just the start. Heating and energy use is the long-term source of carbon emissions in housing – it accounts for 18% of the UK’s total emissions. Even homes made with sustainable materials will leak heat and guzzle electricity if poorly designed.

Stephen Berry, a research fellow at the University of South Australia, argues that our ancestors knew how to design homes that could regulate temperature without energy and regardless of the climate.

Some 2,300 years before the first electric refrigerator, Persians engineered cold storage units that made ice available year-round even through scorching desert summers. Flickr/davehighbury

Some 2,300 years before the first electric refrigerator, Persians engineered cold storage units that made ice available year-round even through scorching desert summers. Flickr/davehighbury

By implementing design features that capture cool air and keep rooms aerated, Iranian architects were leading the world in zero-carbon home design – more than a thousand years before people started thinking about the emissions from their home energy use.

Wind towers allowed Iranian architects to drop interior temperatures several degrees a millennium before the invention of air conditioning. Flickr/nomenklatura

Wind towers allowed Iranian architects to drop interior temperatures several degrees a millennium before the invention of air conditioning. Flickr/nomenklatura

Modern experts in low carbon architecture have developed a standard that strives to ensure all new homes produce as much energy as they consume. There are 400,000 of these “Passivhaus” certified buildings across Europe, and according to David Coley, a professor of low carbon design at the University of Bath, living in a zero-energy home is almost like buying a car that comes with free petrol for life.

So how come Passivhaus homes have heating bills that are a tenth the UK average?

-

Airtight and toasty – Passivhaus homes have much thicker insulation than other houses, with triple glazed windows to trap warm air and mechanical ventilation that can recover and circulate waste heat.

-

Self-powered – By installing solar panels on the roof, Passivhaus homes can produce some of the energy they use.

-

Rigorous and reliable – The Passivhaus scheme requires energy modelling to determine if a home will truly produce as much energy as it consumes. A guarantee that the correct insulation and other features have been delivered and fitted must also be rigorously reported to a third party.

Read more: Labour's low-carbon 'warm homes for all' could revolutionise social housing – experts

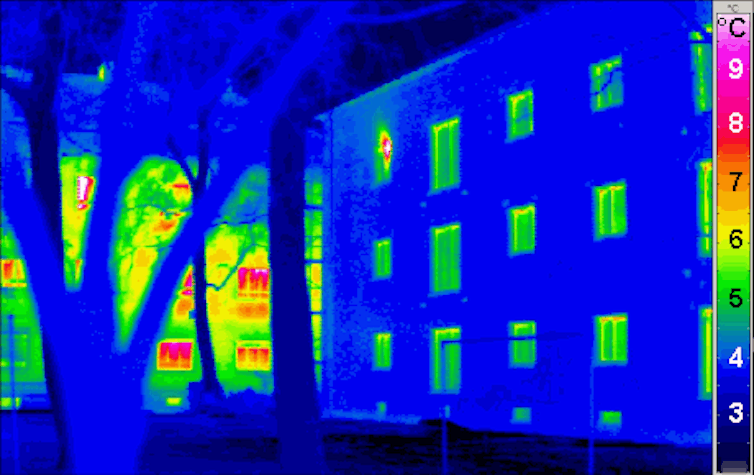

A Passivhaus home (right) leaks less heat than a traditional building (left). Passivhaus Institut/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

A Passivhaus home (right) leaks less heat than a traditional building (left). Passivhaus Institut/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

Decarbonisation starts at home

Retrofit your home

If you’re living in a damp and drafty home that was built long before you were born, you might envy anyone living in a zero-energy new build. While you pay much higher heating bills, a lot of that precious warmth could be lost through poorly insulated walls and windows.

A recent study found that leaky homes are a common problem throughout Europe – particularly the UK, where on average 3°C is lost from homes every five hours during winter. Jo Richardson, professor of housing and social inclusion at De Montfort University, describes how retrofitting existing homes with insulated walls and windows could help make homes more energy efficient and drive down heating bills.

Rethink your gas system

But if a house is still reliant on burning natural gas to heat a water boiler, the source of carbon emissions remains. There are more than 23 million homes with a gas supply for heating and cooking in the UK – an energy burden that amounts to more than double the country’s annual electricity consumption and produces about 60 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions each year.

One way to decarbonise gas heating is to swap the fuel for something zero-carbon, like hydrogen gas. Another is to switch gas-fired boilers and ovens with electrical appliances. Seamus Garvey, professor of dynamics at the University of Nottingham, says that replacing boilers with electric heat pumps would be most energy-efficient:

Electricity can be converted directly to heat with 100% efficiency using cheap resistive elements – the same parts that are present in fan heaters and oil-filled radiators. With this, every terawatt hour (TWh) that’s currently provided by gas heating could be replaced by exactly one TWh of electrical heating.

Heat pumps use electricity to extract the input heat from a nearby river or stream, from the ground or from the air itself. This is known as the “cold source”. The process of extracting heat works similarly to how refrigerators remove heat from food. Delivering a convenient cold source to homes with heat pumps could provide old gas heating networks with an unlikely zero-carbon future, as Garvey explains:

Rather than delivering natural gas to homes, the gas network would deliver water from which domestic heat pumps could extract heat … A house could take in water, extract heat from the water so that it forms ice slurry and dump the slurry down the drain where it would melt again … Some of the water … could be the “grey water” from the house itself – the outflows from showers, baths, dishwashers and washing machines.

In temperate countries, water is often plentiful during winter and could be a useful source of heat. Majivecka/Shutterstock

In temperate countries, water is often plentiful during winter and could be a useful source of heat. Majivecka/Shutterstock

Read more: We can decarbonise the UK's gas heating network by recycling rainwater – here's how

Recycling rainwater to help run electric heating is one (particularly creative) way of decarbonising energy use in homes, but it doesn’t count for much if the electricity came from burning fossil fuels.

Produce your own renewable energy

Over the last two decades, electricity grids have changed to accommodate “prosumers” – homes that produce and consume their own renewable electricity, often using rooftop solar panels or other sources of “microgeneration”, like small wind turbines.

Energy cooperatives have formed between neighbours, where homes can generate, store, and trade energy with each other. “One house can buy excess renewable generation from a neighbour’s solar panels, or from a community wind turbine,” says Merlinda Andoni, a research associate in smart energy systems at Herriot-Watt University.

Own energy production (with your community)

Community ownership of energy production has proven a successful model for increasing renewable generation, according to Iain MacGill and Franziska Mey, energy experts at the University of New South Wales and the University of Technology Sydney.

Germany reached 32% renewable electricity in 2015 with a target of 40% to 45% by 2025, and has some 850 energy cooperatives. Almost half of its installed capacity is owned by households, communities and farmers.

Roofs in the Vienna suburbs are dotted with solar panels. Trabantos/Shutterstock

Roofs in the Vienna suburbs are dotted with solar panels. Trabantos/Shutterstock

Denying the state a monopoly on renewable energy could win supporters that are usually sceptical of government efforts to limit climate change. Sarah Mills is a project manager for National Surveys on Energy and Environment at the University of Michigan. Her research found that Iowa, Kansas and Oklahoma – all states which voted for Donald Trump in 2016 – lead the US in renewable energy generation, with more than 30% of the power generated in each of these states coming from wind turbines and other renewable sources. Three nearby Great Plains states, Nebraska, South Dakota and North Dakota – all solid Republican – are also in the top ten. As Mills explains:

Many communities in these states see renewable energy as an economic opportunity … What that means is that conservatives like wind and solar power. They just don’t want the government to tell them that they must use renewable energy.

In time, you could become part of the ‘civic’ energy sector

Individual households generating energy and distributing it among communities with support from local authorities – this “civic” energy sector could become a dominant model for energy generation in the future according to Stephen Hall, a research fellow in energy economics and policy at the University of Leeds. It’s what energy systems might look like if “the move to a low-carbon society [isn’t] left to governments and big energy companies”, Hall says, and letting homes lead the way could have major benefits:

-

Smarter energy grid – Fewer big power plants would be needed if electricity generation came from multiple sources, disrupting centralised monopolies. Smart distribution systems could regulate this supply efficiently by, for example, providing electricity generated from solar panels on an empty house to busy schools and offices nearby.

-

Pay when you use, not how much – Energy utilities currently set consumers’ tariffs according to the volume of energy they use. This system means it’s not in the interest of the energy producer to help people reduce their demand or become more energy efficient. A smarter, decentralised system could instead charge customers according to when they use energy.

-

Think local – Local authority energy companies could charge residents for services such as “having a warm home” or “hot water”. This would encourage authorities to keep homes warm and well lit as cheaply as possible – promoting energy efficiency.

Read more: No more big power plants? Civic energy could provide half our electricity by 2050

Overhaul housing entirely

Regardless of collective ambition on climate change, housing will have to change drastically in many places in the years ahead to help people resist the world outside. In the UK, 1.8 million people currently live in areas that are at significant risk of flooding – and their flood risk is likely to increase as the climate warms. According to Hannah Cloke, professor of hydrology at the University of Reading, we may need to consider:

Radical practices from parts of the world that flood more frequently … such as houses that are designed to float when floods come, rising on stilts as the water rises … There are less dramatic adaptations that can be made. Internally reinforced, mechanically sealable flood doors … Waterproof concrete and stone-slab floors. Electrical sockets can be raised and non-return valves can be fitted to toilets to stop sewage filling homes when it floods.

As Cloke explains, the fact that so many people live on floodplains in the UK is a reminder of how ill-prepared we are for the upheavals that climate change will bring. Homes – places of refuge and safety – could become the very opposite as old certainties suddenly disappear.

Read more: Housebuilding ban on floodplains isn't enough – flood-prone communities should take back control

Rather than retreat into bunkers fortified with solar panels and flood doors, Matthew Paterson, professor of international politics at the University of Manchester, highlights that the roots of modern housing policy elicit a collective response.

The ‘great acceleration’ in greenhouse gas emissions [that occurred] during and after World War II [in the US] … was sustained by the expansion of consumption – most directly by the shift to mass car ownership and urban sprawl that ‘locked in’ high fossil energy use, not only in transport but in housing.

Concrete jungles filled with the cars – housing policy has tended to ‘lock in’ high consumption, high emission lifestyles. John Wollwerth/Shutterstock

Concrete jungles filled with the cars – housing policy has tended to ‘lock in’ high consumption, high emission lifestyles. John Wollwerth/Shutterstock

If housing policy has nurtured high-energy lifestyles, by encouraging people to live in dense suburbs with at least one car on the drive, Richard Kingston and Ransford Acheampong, experts in urban planning at the University of Manchester, believe it can be re-engineered to encourage ways of living that are healthier for people and the planet:

We need to build high density, mixed-use developments with affordable housing and excellent green spaces … Provide basic services within walking distance, create safe spaces for people to walk and provide public transit that uses clean energy.

Further reading

Click here to subscribe to our climate action newsletter. Climate change is inevitable. Our response to it isn’t.

Jack Marley, Commissioning Editor, Environment + Energy, The Conversation

Image: A Passivhaus home (right) leaks less heat than a traditional building (left). Passivhaus Institut/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.